It may be the best-known of the transportation brands in the sharing economy, but the absence of Uber Canada didn’t stop a group of Canadian startups from addressing some of the questions of trust that will determine the adoption of ridesharing apps and autonomous vehicles.

In a panel discussion held at Ryerson University’s Digital Media Zone (DMZ) late last week, experts suggested that while technology is rapidly changing the options available for Canadians trying to get from A to B, those offering ridesharing services or self-driving cars may have significant preconceptions to overcome.

“Almost everyone I’ve ever talked to who has a visceral reaction against using Uber has never used the service,” said Paul Barter, a professor with the Schulich School of Business and co-author of a sharing economy book titled The Uber Of Everything. “Over time, the market chooses, right? We decide to trust an organization and ride with them because they’re thoughtful, they offer us a female driver if that’s what we want. . . or we don’t.”

An Uber ad from 2015

While persuading skittish travellers may take a major marketing push, some existing trends in popular culture may help, suggested Arash Barol, general manager of BlancRide. Somewhat like UberX, BlancRide is a carpooling app that lets people offer their passenger seat or other room in the car to those travelling on the same route.

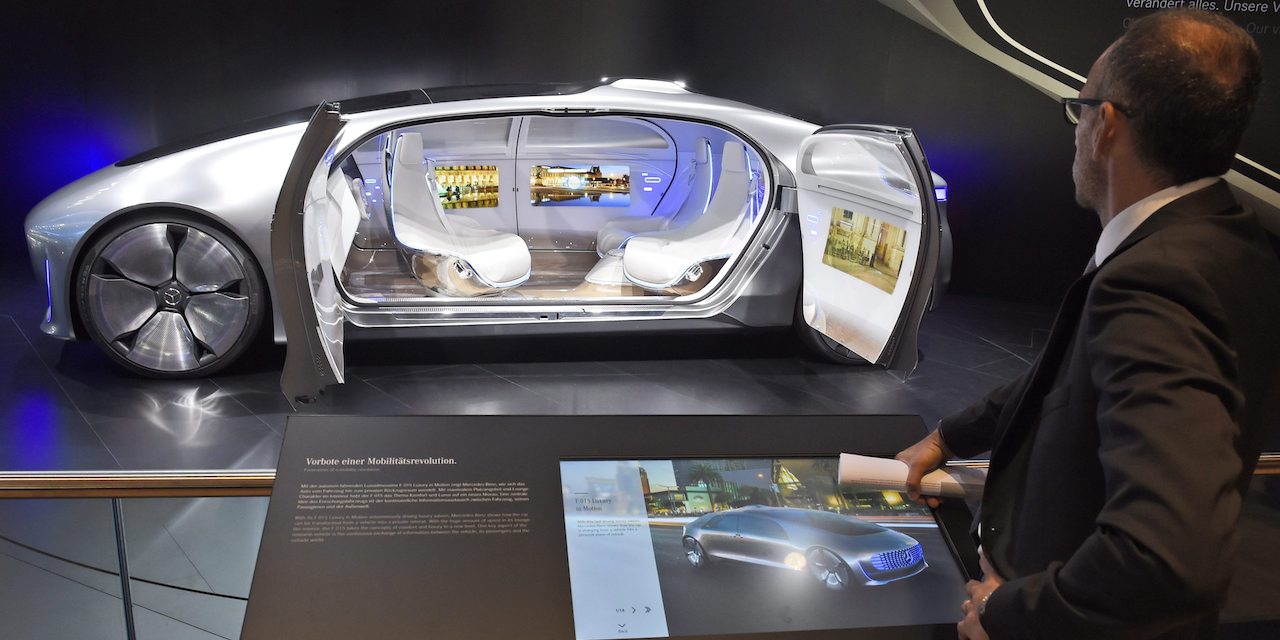

“There’s this shift where we all don’t have to buy individual things but share the extra capacity that is unused,” he said. “Autonomous vehicles is an opportunity where it can enable the sharing economy (even more).”

This includes not only sharing within vehicles but where they sit idle. That’s the idea behind Rover Parking, which describes its service as similar to AirBnB. Tim Wootton, its co-founder, said building a strong brand in this sector may also be easier as startups have come to an agreement with regulators and municipalities.

“The way we’re moving around cities is about to drastically change,” he said. “Once everybody is talking and communicating and that transparency is there, that’s when you’re going to see mass adoption.”

Those shaping the right brand experience from the outset are likely to prosper, Barter added. “It’s what we call ‘feedback with consequences,’” he said, referring to Uber’s stringent mandate to get at least a four out of five stars from users. “Try going out as an Uber driver and providing a negative experience. You won’t be driving an Uber the next day.”

On the other hand, self-driving cars and ridesharing brand successes will also be shaped in part by our relation with technology itself, argued Barrie Kirk, executive director of the Canadian Automated Vehicles Centre of Excellence (CAVCOE). He told a story about an early Google prototype of an autonomous vehicle where beta-testers were given detailed briefings and instructed to pay attention to where the car was going at all times.

“They did all sorts of things like reading or surfing the web,” he said. “Even the most nervous people very quickly learned to trust the technology. The success of the technology was it’s failure.”

Not that traditional transportation technology is any better, of course. Although Uber Canada’s general manager was invited to the panel discussion, he was waylaid by — you guess it — travel issues, albeit a flight rather than a vehicle.